Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos has appointed a team of senior government officials to launch talks with the opposition on changes to a peace deal with the Farc rebel group.

Mr Santos made the announcement after meeting with political party leaders.

The peace deal was rejected by a narrow margin in a referendum on Sunday.

Former President Alvaro Uribe, who led the “no” campaign, did not attend the meeting but appointed three negotiators to hold talks with the government.

Mr Uribe, a senator and leader of the Democratic Centre party, wants rebels who committed serious crimes to serve prison sentences and for some of the Farc leaders to be banned from politics.

The peace deal was signed last week after nearly four years of negotiations, which were held in the Cuban capital, Havana.

For the agreement to be implemented, putting an end to 52 years of conflict, it would have had to be ratified by the Colombian people in a referendum.

Pre-election polls had indicated a strong victory for the “yes” camp.

But in a surprise result, 50.2% of voters rejected the agreement.

The difference was about 54,000 votes out of almost 13 million ballots. Turnout was low with fewer than 38% of voters casting their votes.

President Santos said last week there was no “Plan B” for ending the conflict, which has killed about 260,000 people.

Since the result has been announced, however, both Mr Santos and the Farc have affirmed their determination to continue working to secure a peace deal.

“I will not give up, I will keep seeking peace until the last minute of my term,” he said in address after the results were announced.

Farc leader Timoleon Jimenez, better known as Timochenko, said the rebels would continue to abide by a bilateral ceasefire agreed with the Colombian government.

The chief peace negotiator for the government, Humberto de la Calle, offered to resign earlier on Monday, saying he took “full responsibility for any errors in the negotiation”.

He was earlier ordered back to the Cuban capital of Havana to work with rebel leaders on modifying the deal.

Mr Santos rejected his resignation and, instead, appointed him to lead the “national dialogue” team that will try to save the peace process.

The other two members in Mr Santos’s team are Foreign Minister Maria Angela Holguin and Defence Minister Luis Carlos Villegas.

Mr Uribe appointed three senior politicians from his party for the talks: Oscar Ivan Zuluaga, Carlos Holmes Trujillo and Ivan Duque.

Who voted how?

Image copyrightAFP

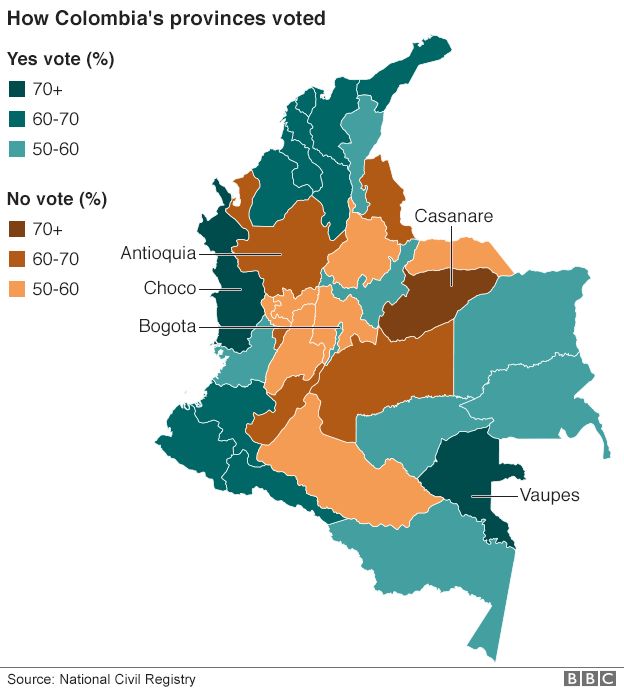

Image copyrightAFPColombia was divided regionally with most of the outlying provinces voting in favour of the agreement and those nearer the capital and inland voting against it.

In Choco, one of the provinces hardest hit by the conflict, 80% of voters backed the deal. The capital, Bogota, also voted “yes” with 56%.

But in the eastern province of Casanare – where farmers and landowners have been extorted for years by the Farc – 71.1 % rejected the deal.

Most of those who voted “no” said they thought the peace agreement was letting the rebels “get away with murder”.

Under the deal, special courts would have been created to try crimes committed during the conflict.

Those who confessed to their crimes would have been given more lenient sentences.

Many Colombians also balked at the government’s plan to pay demobilised Farc rebels a monthly stipend and to offer those wanting to start a business financial help.

“No” voters said this amounted to a reward for criminal behaviour while honest citizens were left to struggle financially.

Others were unhappy that under the agreement, the Farc would be guaranteed 10 seats in Congress.